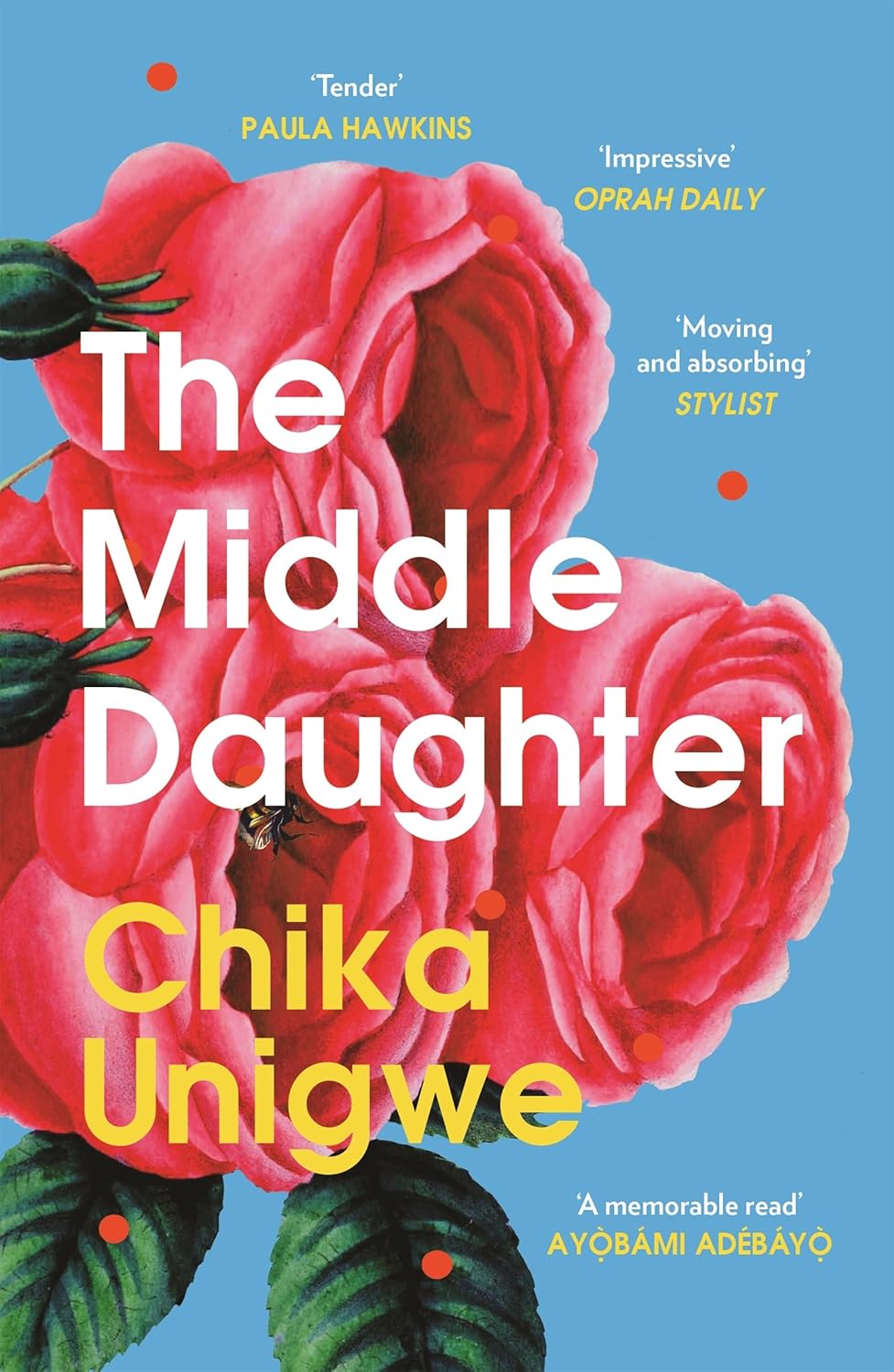

The Middle Daughter by Chika Unigwe: The Plight of a Girl Abandoned

Before attending the book reading at RovingHeights, Lagos, I had heard of Chika Unigwe but hadn’t read any of her novels. What piqued my curiosity was the title of her book: The Middle Daughter. As a daughter myself (albeit not the middle one), I am fascinated by books that chronicle experiences from that perspective. Wherever there are daughters, it is inevitable to find fathers and mothers and in my quest to comprehend the diverse dynamics of these relationships, particularly in the context of mother-daughter bonds, I am drawn to these stories.

The premise itself is intriguing, ‘modern reimagining of the myth of Hades and Persephone within a Nigerian family’. One the author specifically says she wrote to provide a satisfying conclusion, one that offers a sense of happiness and resolution—an ending that Persephone, in the original myth, did not have the privilege of experiencing. I had spent years of my adolescence consuming Greek mythology stories, but admittedly, I had to search to refresh my memory of the Hades and Persephone myth, all of which I recalled was its link to the changing of the seasons and the abduction of Persephone. Here’s a summary:

Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, the goddess of agriculture and fertility, was a beautiful young maiden. One day, while Persephone was gathering flowers in a meadow, the earth suddenly split open, and Hades, the god of the underworld, emerged in his chariot. He swiftly abducted Persephone and took her to the underworld to be his wife.Demeter, devastated by the loss of her daughter, wandered the earth in search of her. During this time, she neglected her duties as the goddess of agriculture, causing crops to wither and famine to spread across the land. The gods and mortals suffered greatly, and in response, Zeus decided to intervene.

Zeus sent Hermes, the messenger of the gods, to the underworld to negotiate with Hades. After much discussion, it was agreed that Persephone would spend half of the year with Hades as his queen and the other half with her mother on Earth. This arrangement would restore balance and allow for the flourishing of crops during Persephone’s time on Earth.Thus, when Persephone returns to her mother, Demeter, in the spring, Demeter rejoices, and the earth blooms with vibrant life. This period is known as spring and summer. However, when Persephone returns to the underworld in the fall, Demeter grieves, and the earth becomes barren and cold, causing winter to descend upon the world.

What stands out to me in the myth is the depiction of a mother’s love for her daughter that materializes as her profound grief in the event of the daughter’s kidnapping. A love so powerful, she disregards her godly responsibilities and lets the world plunge into famine. It is this great grief that propels the intervention of Zeus and begets the celebration that marks Persephone’s time on Earth as a celebration—spring.

I expected this loose retelling to incorporate the key elements: an older man who lures a young girl away from the life she’s known with her family, long-term separation from family, a grieving mother who does all to ensure she’s returned. The novel stays true to the myth on some levels but its divergence from it, raises questions in my mind.

The book opens from the POV of an omniscient narrator who we’ve yet to meet. This narrator, Udodi tells a creation story that begins with curiosity causing chaos. The timeline oscillates between the present and the past and shifting POVs. Nani, the middle daughter, paints the picture of family life at Umuomam Estate, House Number 47. The household consists of three girls, their father, and mother, who are comfortable, middle-class parents. The girls—Udodi, Nani, and Ugo—consider their father, Doda, an affectionate parent, whom they favour over their mother. Mother also applauds Doda for not being ‘the sort to kick his wife out for giving him only girls’.

Sadly, the hands of grief doubly touch the family. They lose their oldest child, the first daughter, Udodi in the most unexpectant manner. The author guides us through the experience of this grief, starting from the heart-wrenching moment the family learns about the daughter’s passing and delving into the complex ways it impacts their family dynamic. Each family member processes their grief in unique and individual ways. ‘After Udodi died, things fell apart. Everything took longer to do; it was as if my body moved in slow motion. I conserved my breath by hardly speaking to anyone. Not even Ebubedike. Doda slouched, carrying his grief on his shoulders. Mother’s was in her eyes, in the way they settled on you without seeing you. Ugo cried so much it seemed as if she would never stop.’

Two years later, Doda passes after a short stint with illness and Nani handles his loss the hardest. Time splits at House Number 47 between pre-Doda and post-Doda. The surviving members of the family have to navigate life and the new vulnerabilities their peculiar circumstances have opened them up to. I know this story, I’ve lived this story. Prying relatives who have come to enforce the Igbo tradition of inheritance upon the passing of a son disguised as coming ‘to see how my brother’s family is doing’; the mother’s fear of the judgment by society as a widow with two girls and her worry for their well-being.

Grief rests at the core of the plot. Two deaths leave the family vulnerable in ways they could not have envisaged. As is often the case, it tears at the fabric of the family. Nani is dissatisfied with how quickly Mother and Ugo seemed to have moved on and from Doda’s death.

Post-Doda, things happen quickly. Nani refuses to sit for the SATs (fueled by teenage rebellion and resignation due to grief as well as the fear of being far away from family). The sisters squabble now more than ever. Mother decides to open a maternity clinic. Nani meets Ephraim.

Enter Ephraim. A French-Cameroonian bumbling preacher with poor English skills who doesn’t come across as inherently evil. This in itself is not unsurprising as hypocrisy and villainy can exist even within the confines of religion. He meets Nani by the gate of her family home as she gathers roses from the rose bush—a reference to how Hades meets Persephone. They discuss faith, grief and family and form a friendship that culminates in him sexually assaulting Nani and eventually getting married to her. Everything changes from this point.

The characters unravel in a way that belies the depth of their characterization and the decisions they make are far from believable even when you examine them against the backdrop of the myth the story is loosely based upon.

There are three girls in the story: the first, middle and last daughter and we get the perspectives of all three in the plot. Unigwe examines the power dynamics that can emerge between siblings. Nani, as narrator, reflects on her relationship with her sisters, highlighting the subtle forms of dominance that can arise in sibling interactions. Unigwe portrays the tug-of-war between autonomy and dependence, as siblings navigate their individual identities while simultaneously being shaped by their shared experiences. This way, the novel portrays the dance of closeness and distance, as siblings both support and challenge one another, often mirroring the intricate nature of familial bonds. Ugo hates Nani for breaking up their even smaller family unit by ‘choosing’ Ephrain but loves Nani in the same vein. She feels responsible for Nani’s choice, her guilt dripping from her narration. She goes to persuade her on numerous occasions to return home.

Mother is integral to the plot but somehow, sits at the cusp of it. I’m inclined to think that this was Unigwe setting the scene for Mother’s decision to cast her 17-year-old aside without any discernible justification and her ethically questionable practice. This may also be why Mother remains unnamed. Nani alludes to the relationship between the girls and their mother in the beginning: ‘Our mother is somewhere in the house but it is Doda that we seek out. It is only Doda. It was with him that I first felt safest. Even now, when he’s no longer here, I will not go to Mother.’

We sympathize with Mother when she loses Udodi, her first daughter. Her grief is palpable and when Doda dies, we get a glimpse of the extent of her burden—her bemoaning societal expectations of a widow with only daughters. However, Mother’s relationship with Nani is coloured with nuanced tension that can often permeate mother-daughter relationships. This is also evident in her relationship with the last daughter, Ugo. Ugo tries to keep the peace, adhering to her mother’s commands to stop visiting Nani, following her to America and offering her a hand in forgiveness.

Mother’s reaction to Nani’s resolve to be coupled with Ephraim, who’s practically a stranger and her ensuing abandonment of Nani to the fate she’s supposedly chosen especially given her age raises eyebrows. This is a stark deviation from the demeanour of Demeter, Persephone’s mother in the myth and a direct contradiction to the cultural norms of where the book is set. It becomes even more baffling when you recall that the family is depicted as financially well-off and capable of leaving the country due to the girls’ American citizenship. Additionally, Mother’s newfound role as owner of the maternity clinic positions her in the corridors of power with which she could have intervened and put an end to the abusive situation that Nani endured for an extended period of time. The abusive tactics employed by Ephraim were plausible, but the events leading up to it and her mother’s response are unrealistic and nothing short of bizarre. In this, we never truly understand her or her motivations.

Style-wise, the choice to have the older sister narrate in the voice of an all-seeing, all-knowing being delivering a chorus did not appear to serve a significant purpose in driving the overall plot. Initially, I believed this narrative approach would enhance the sense of foreboding and provide insights into the characters’ motivations. One might argue that it’s done in a bid to mirror the choruses of classical Greek tragedies. Moreover, the abrupt transition from first person to third person in different perspectives makes it challenging to recognize when the shift has taken place.

The question remains: Have we been delivered a true happy ending if we can trace the reason for the length of Nani’s suffering to her mother’s initial abandonment? Is shame culture justification enough for Mother’s choices?

While reading, you might feel a lot of anger, understandably so. Nevertheless, the prose flows smoothly, allowing for a rapid pace of reading. Personally, I found myself indifferent to the story and unable to grasp a firm understanding of the characters, but, embedded within the storytelling lies an important message about the immense difficulty victims face in breaking free from their abusers, compounded by the enabling nature of society often compounded by the lack of communal support.

My heart hurt for Nani, and it made me reflect on all the others like her, alone and scared, desperately longing for someone to help bring them back home.